Myocardial infarction

Part of the heart muscle is deprived of oxygen. If this continues it will die. The patient may, even before then. Nowadays, we have the technology to reverse the former.

Contents |

Introduction

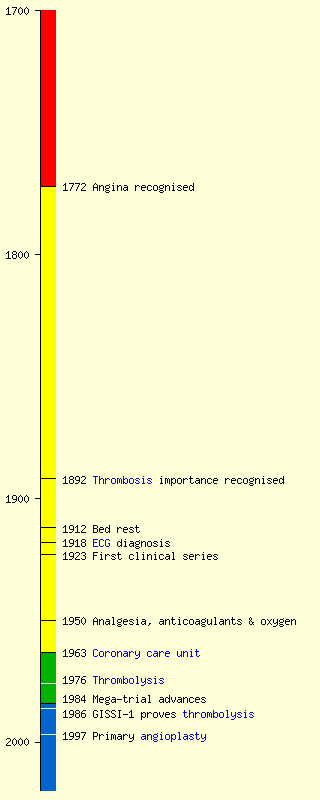

Acute coronary syndrome describes the spectrum of ischaemic heart disease presentations from ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI or simply MI) covered further in this article to non ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (NSTEMI). These conditions are well covered by high quality up to date open access guidelines such as those from European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence(NICE) and the reader should refer to these for a detailed review and understanding of the subject. Myocardial infarction with survival was described between 1878 and 1918 - see timeline below.

Aetiology

Almost invariably the cause is occlusion of part of the coronary arterial circulation as a result of a clot forming from, on and downstream of an atherosclerotic lesion in the wall of the artery, a plaque. Much information about the initial process of atheromatous lesion formation exists, but lacks a wholly convincing narrative to tie it together. Plaques may persist for long periods, they may regress, at least in young generally healthy people whose coronary arteries have been imaged incidentally and they may, for reasons which are unclear, suddenly progress to activating platelets on their surface, triggering a coagulation cascade and occlusion consequent upon that.

Lipids - cholesterol - appear to be involved in the plaque-forming process.

Clinical

The classic presentation is with severe pain of a gripping, squeezing or pressing nature in the centre of the chest, which commonly radiates to the left upper arm, not uncommonly to the jaw and sometimes to the epigastrium. The patient is ill, is obliged to cease activities, appears pale and sweats. There has often been some prodromal episode of pain which was not so bad, nor so long.

| A normal ECG does not exclude MI |

Presentations other than classic are common, and modern medical thought favours a high degree of suspicion, rapid admission, monitoring and biochemical testing, and rapid discharge if MI or angina is excluded. Management of typical presentations should in general be based on consensus guidelines, which can be local, national or international[1]

| An absence of risk factors does not reduce the likelihood of an MI in a patient with signs and symptoms suggestive of the diagnosis.[2] |

Criteria

- Old WHO criteria: 2/3 (history, ECG and cardiac enzymes) becoming increasing problematical by [3]

-

Universal definition based on troponin as biomarker[4][5].

- This increased diagnosis by 25% but provided criteria that proved to be an independent predictor of long term mortality[6]

- As of third universal definition[7]

| In sudden unobserved death in patients with previously known Ischemic Heart Disease, myocardial infarction is not the most likely cause, a sudden acute cardiac failure following reduction of coronary perfusion pressure below a critical value or a dysrhthymia is. In the absence of more clear indication of an actual MI, it is desirable to give a cause of death as IHD rather than assume an MI occurred. |

ECG

- Characteristic ECG changes if present interpreted in patient context

Blood tests

- Troponin serial levels interpreted in patient context

Radiology

- CXR

- Angiography (increasingly incidental result of primary PCI in ST elevation MI)

Treatment

Prevention

-

Targeted primary prevention does work and is resource effective in:

- Smoking

- Hypertension

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hypercholesteraemia (certainly in males with statins)

- Other lipid disorders

Medical

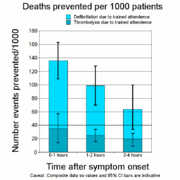

- Defibrillation - this is actually the most effective technology after the event and tends to be overlooked as an established technology and most early fatalities occur before hospitalisation. Improving access times to thrombolysis actually benefits more patients by giving them prompter access to a defibrillator.

- In ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) primary PCI is superior to thrombolysis in the first 2 hours after presentation[8]

- Thrombolysis provided certain criteria are met. Thrombolysis can be combined with late PCI in the window 1 to 3 hours for superior outcome[9].

- Immediate revascularisation may be superior, but is more complicated and expensive and has some of its own problems and complications.

Treatment after infarction

ACE inhibitors such as Ramipril, platelet aggregation suppressors such as Clopidogrel and of course Aspirin and a beta-adrenergic -blocker such as typically Bisoprolol for varying periods and a statin such as Simvastatin for ever variously improve the remodelling of an injured ventricle; avoid further occlusions; resist a misbalance between oxygen supply and demand at the myocardium and make people less likely to have heart failure and subsequent infarctions. Treatment may be a balance between the ideal according to theory and what the patient can tolerate.

Surgical

Rehabilitation

Historical

The condition was not recognised in life for years because:

- It had no specific clinical signs

- Dogma had it that myocardial damage was uniformally fatal

- Clinicians had no diagnostic test so tended to say so what (still a tendency today with any condition without objective criteria !)

- 1772 William Heberden describes angina.

- 1878 Adam Hammer describes a clinicopathological correlation consistent with survival after myocardial infarction[10][11]

- 1882 Julius Cohnheim notes myocardial infarction not uniformally fatal[12]The occlusion of a coronary artery - in case it does not prove fatal . . . leads to the destruction of the contractile substance of that portion of the heart which is fed by the affected artery, and afterwards to the formation there of so-called myocarditic indurations.

- 1892 William Osler describes myocardial infarction due to either thrombosis or embolism[13]

- 1893 John Steven as a pathologist publically notes continued lack of clinical interest in this important condition[14][15].

- 1899 Ludwig Hektoen recognises that cardiac infarction caused more frequently by thrombosis than embolism [16]

- 1901 Krehl first describes non-fatal myocardial infarction [17]

- 1910 Obraztsov and Strazhesko describe non-fatal myocardial infarction.[18]

- 1912 James Herrick presents the classic signs and symptoms of myocardial infarction and recommends bed rest[19]

- 1918 ECG correlation described[20]

- 1923 Clinicopathological series of 19 patients[21]

- 1939 41 years of controversy due to only 31% of patients who had evidence of myocardial necrosis on autopsy also (still) having coronary thrombosis [22]

- 1957 Intravenous streptokinase first used successfully in man (in context of dogma and allergy risk not pursued)[23]

- 1960 CPR by closed chest cardiac massage[24]

- 1961 Intensive central monitoring proposed[25]

- 1963 Coronary care unit [26]

- 1968 First description of successful CABG[27]

- 1970 Swan Ganz catheter allows physiological understanding (later proved to increase mortality when used routinely)[28]

- 1972 Dog models suggest reperfusion will minimise ischaemic myocardial damage. [29][30]

- 1976 Chazov in Russia first tries intracoronary streptokinase in man after diagnostic angiography.[31]

- 1977 First statin tried in man (in patient with unstable angina)[32]

- 1979 First English language report of intracoronary streptokinase[33]

- 1979 Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in man described[34]

- 1980 First human evidence of thrombosis in vivo noted by Marcus DeWood[35]

- 1984 Acute betablockade useful [36]

- 1986 GISSI shows iv streptokinase works[37]

- 1988 Acute aspirin improves survival (ISIS-2)[38]

- 1992 ACE inhibitors improve survival[39]

- 1997 Primary angioplasty can be superior to thrombolysis [40]

External Links

- Braunwald E. Evolution of the management of acute myocardial infarction: a 20th century saga. Lancet 1998; 352:1771-1774[41]

- Fye WB. The delayed diagnosis of myocardial infarction: it took half a century! Circulation. 1985;72(2):262-71.[42]

The Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation. European Heart Journal, doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehn416 free full text pdf [43]

References

- ↑ The Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation. European Heart Journal, doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehn416

- ↑ Body, R., G. McDowell, et al. "Do risk factors for chronic coronary heart disease help diagnose acute myocardial infarction in the Emergency Department?" Resuscitation 79: 41-45.

- ↑ Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. Myocardial infarction redefined--a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. Sep; 36(3):959-69.

- ↑ Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Jaffe AS, Apple FS, Galvani M, Katus HA, Newby LK, Ravkilde J, Chaitman B, Clemmensen PM, Dellborg M, Hod H, Porela P, Underwood R, Bax JJ, Beller GA, Bonow R, Van der Wall EE, Bassand JP, Wijns W, Ferguson TB, Steg PG, Uretsky BF, Williams DO, Armstrong PW, Antman EM, Fox KA, Hamm CW, Ohman EM, Simoons ML, Poole-Wilson PA, Gurfinkel EP, Lopez-Sendon JL, Pais P, Mendis S, Zhu JR, Wallentin LC, Fernández-Avilés F, Fox KM, Parkhomenko AN, Priori SG, Tendera M, Voipio-Pulkki LM, Vahanian A, Camm AJ, De Caterina R, Dean V, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Funck-Brentano C, Hellemans I, Kristensen SD, McGregor K, Sechtem U, Silber S, Tendera M, Widimsky P, Zamorano JL, Morais J, Brener S, Harrington R, Morrow D, Lim M, Martinez-Rios MA, Steinhubl S, Levine GN, Gibler WB, Goff D, Tubaro M, Dudek D, Al-Attar N. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. Nov 27; 116(22):2634-53.(Link to article – subscription may be required.)

- ↑ Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Jaffe A, White HD. The universal definition of myocardial infarction: a consensus document: ischaemic heart disease. Heart (British Cardiac Society). Oct; 94(10):1335-41.(Link to article – subscription may be required.)

- ↑ Costa FM, Ferreira J, Aguiar C, Dores H, Figueira J, Mendes M. Impact of ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF universal definition of myocardial infarction on mortality at 10 years. European heart journal. Oct; 33(20):2544-50.(Link to article – subscription may be required.)

- ↑ Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD, Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Jaffe AS, Katus HA, Apple FS, Lindahl B, Morrow DA, Chaitman BR, Clemmensen PM, Johanson P, Hod H, Underwood R, Bax JJ, Bonow RO, Pinto F, Gibbons RJ, Fox KA, Atar D, Newby LK, Galvani M, Hamm CW, Uretsky BF, Gabriel Steg P, Wijns W, Bassand JP, Menasché P, Ravkilde J, Ohman EM, Antman EM, Wallentin LC, Armstrong PW, Simoons ML, Januzzi JL, Nieminen MS, Gheorghiade M, Filippatos G, Luepker RV, Fortmann SP, Rosamond WD, Levy D, Wood D, Smith SC, Hu D, Lopez-Sendon JL, Robertson RM, Weaver D, Tendera M, Bove AA, Parkhomenko AN, Vasilieva EJ, Mendis S, Bax JJ, Baumgartner H, Ceconi C, Dean V, Deaton C, Fagard R, Funck-Brentano C, Hasdai D, Hoes A, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, McDonagh T, Moulin C, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Vahanian A, Windecker S, Morais J, Aguiar C, Almahmeed W, Arnar DO, Barili F, Bloch KD, Bolger AF, Bøtker HE, Bozkurt B, Bugiardini R, Cannon C, de Lemos J, Eberli FR, Escobar E, Hlatky M, James S, Kern KB, Moliterno DJ, Mueller C, Neskovic AN, Pieske BM, Schulman SP, Storey RF, Taubert KA, Vranckx P, Wagner DR. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. European heart journal. Oct; 33(20):2551-2567.(Link to article – subscription may be required.)

- ↑ Bhatt DL. Timely PCI for STEMI - Still the Treatment of Choice. The New England journal of medicine. Mar 10.(Link to article – subscription may be required.)

- ↑ Armstrong PW, Gershlick AH, Goldstein P, Wilcox R, Danays T, Lambert Y, Sulimov V, Ortiz FR, Ostojic M, Welsh RC, Carvalho AC, Nanas J, Arntz HR, Halvorsen S, Huber K, Grajek S, Fresco C, Bluhmki E, Regelin A, Vandenberghe K, Bogaerts K, Van de Werf F. Fibrinolysis or Primary PCI in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. The New England journal of medicine. Mar 10.(Link to article – subscription may be required.)

- ↑ Hammer A: Ein Fall von Thrombotischem Verschlusse Einer der Kranzarterien des Herzens. Weiner Med Wochenschr 28: 97, 1878

- ↑ Hammer A: Thrombosis of one of the coronary arteries of the heart diagnosed during life (translated by Workman J). Can J Med Sci 3:353, 1878

- ↑ Cohnheim J: Lectures on general pathology (Translated from the German ed 2 by McKee AB). London, 1889, New Sydenham Society

- ↑ Osler W . The Principle and Practice of Medicine. : D. Appleton; 1892

- ↑ Stevens JL: The pathology of fibroid degeneration (fibrous transformation) of the heart, with twenty-one cases. J Pathol Bacteriol 2: 190, 1894

- ↑ Steven JL: Lectures on fibroid degeneration and allied lesions of the heart, and their association with diseases of the coronary arteries. Lancet 2: 1153; 1205; 1255; 1305, 1887

- ↑ Attrib to Hektoen L - anonymous Infarction of the heart. JAMA 1899;33:919

- ↑ Krehl L. Die Ekrankungen des Herzmuskels und die Nervosen Herzkrankheiten. Vienna: Alfred Holder, 1901:

- ↑ Obrastzov WP, Strazhesko ND. Zur Kenntnis der Thrombose der Koronararterien des Herzens. Z Klin Med 1910; 71: 116-132.

- ↑ Herrick JB . Clinical features of sudden obstruction of the coronary arteries. JAMA 1912; 59: – 20.

- ↑ Smith FM. The ligation of coronary arteries with electrocardiographic study. Archives Internal Medicine 1918;22:8-27.

- ↑ Wearn JT. Thrombosis of the coronary arteries, with infarction of the heart. Am J Med Sci 1923; 165: 250-276.

- ↑ Friedberg CK, Horn H . Acute myocardial infarction not due to coronary artery occlusion. JAMA 1939; 112: 1675– 9.

- ↑ Sherry S, Fletcher A, Alkjaersigm N, Smyrniotis F . An approach to intravascular fibrinolysis in man. Trans Assoc Am Physicians 1957; 70: 288– 96

- ↑ Kouwenhoven WB, Jude JR, Knickerbocker GG. Closed-chest cardiac massage. JAMA 1960; 173: 94-97

- ↑ Julian DG. Treatment of cardiac arrest in acute myocardial ischemia and infarction. Lancet 1961; ii: 840-844.

- ↑ Day H. An intensive coronary care area. Dis Chest 1963; 44: 423-427

- ↑ Favaloro RG, Effler DB, Groves LK, Fergusson DJ, Lozada JS. Double internal mammary artery-myocardial implantation. Clinical evaluation of results in 150 patients. Circulation. 1968 Apr; 37(4):549-55.

- ↑ Swan HJC, Ganz W, Forrester J, et al. Catheterization of the heart in man with use of a flow-directed balloon-tipped catheter. N Engl J Med 1970; 283: 447-451

- ↑ Maroko P, Libby P, Ginks W, Bloor C, Shell W, Sobel B, Ross JJ . Early effects on local myocardial function and the extent of myocardial necrosis. J Clin Invest 1972; 51: 2710– 6.

- ↑ Sobel BE, Bresnahan GF, Shell WE, Yoder RD . Estimation of infarct size in man and its relation to prognosis. Circulation 1972; 46: 640– 8.

- ↑ Chazov EI, Matveeva LS, Mazaev AV, Sargin KE, Sadovskaia GV, Ruda MI . Intracoronary administration of fibrinolysin in acute myocardial infarct. Ter Arkh 1976; 48: 8– 19.

- ↑ Endo A. The discovery and development of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Journal of lipid research. 1992 Nov; 33(11):1569-82.

- ↑ Rentrop KP, Blanke H, Karsch KR, Wiegand V, Kostering H, Oster H, Leitz K . Acute myocardial infarction: intracoronary application of nitroglycerin and streptokinase. Clin Cardiol 1979; 2: 354– 63.

- ↑ Grüntzig AR, Senning A, Siegenthaler WE. Nonoperative dilatation of coronary-artery stenosis: percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. The New England journal of medicine. 1979 Jul 12; 301(2):61-8.(Link to article – subscription may be required.)

- ↑ DeWood MA, Spores J, Notske R, Mouser LT, Burroughs R, Golden MS, Lang HT. Prevalence of total coronary occlusion during the early hours of transmural myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(16):897-902.

- ↑ International Collaborative Group. Reduction of infarct size with early use of timolol in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1984; 310: 9.

- ↑ Effectiveness of intravenous thrombolytic treatment in acute myocardial infarction. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Streptochinasi nell'Infarto Miocardico (GISSI). Lancet 1986; 8478: 397– 402.

- ↑ ISIS-2 Collaborative Group. Randomized trial of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither among 17 187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-2. Lancet 1988; i: 349

- ↑ Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E, Moye LA, et al. Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Results of the Survival and Ventricular Enlargement Trial. N Engl J Med 1992; 327: 69-77.

- ↑ Weaver WD, Simes RJ, Betriu A, et al. Comparison of primary coronary angioplasty and intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 1997; 278: 2093-2098.

- ↑ Braunwald E. Evolution of the management of acute myocardial infarction: a 20th century saga. Lancet 1998; 352:1771-1774

- ↑ Fye WB. The delayed diagnosis of myocardial infarction: it took half a century! Circulation. 1985;72(2):262-71.

- ↑ The Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation. European Heart Journal, doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehn416