Weekend morbidity and mortality experiments

(Redirected from Weekend effect)

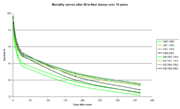

Differental mortality for four year cohorts of acute myocardial infarction in New Jersey, showing deteriorating survival in the cohort compared to the previous 8 years and differential survival for every 4 year period in favour of weekday admissions rather than weekend (prefix WE) admissions[1]

- Whole population mortality is quite different from institutional mortality and both can be influenced by ease of access to health and social care which in many societies appears likely to vary during the week due to employment and other cultural patterns.

- Accordingly for religious, social and political reasons we have the concept of the working week and weekends. Cultures make varying provision for emergency health care at weekends but usually limit access to certain healthcare resources at weekends. This has been associated with differential mortality in patients with common medical illnesses depending upon what day they are admitted to hospital creating the 'weekend effect' on mortality. The most convincing evidence for such an effect comes from whole population studies. [2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9]. One issue that has to be controlled for, is that patients admitted at weekends are more ill[10]. A common theme in commentary on this issue is that resources necessary to manage the patients are not available at weekends due to logistic reasons. To a degree this can be addressed by systems changes and there is likely to be an optimum resource distribution over time during a week for any health and care system treating a particular condition. Primary care and social care constraints could create an exaggerated weekend effect in secondary care if secondary care resources are used at weekends instead of more effective primary and social care resources. Such patterns have been suggested to be important and need to be considered.

- There is evidence from the UK that the shift in emergency surgical orientated resources and practice in the last 15 years that has resulted in the 30 day mortality rate for emergency surgical admissions falling from 5·4% to 2·9 % during has largely abolished the weekend effect in this speciality[11]. This reduction happened before a recent overt political drive to address the issue.

- With the ever more acutely orientated interventions to treat myocardial infarction this is not unexpectedly the case with this diagnosis. It has been estimated that 9 to 10 deaths per 1000 admissions could be saved by better acute service cover. However some evidence, while it shows ever increasing acute survival, also shows worsening long term survival.[12] An explanation for this is that many recently introduced interventions in acute myocardial infarction are based on short term studies and can have high take up because of the assumption that short term effectiveness translates into long term effectiveness. Modern acute interventions as practised in the Eastern seaboard of the United States while reducing immediate mortality in myocardial infarction patients who make it to hospital could be increasing medium term mortality by up to 30 deaths per 1000 patients treated with part of the issue being time of presentation or relapse. The data is being watched very carefully. By this fear appeared to be justified with respect to access to PCI being reduced at weekends[13][14]. Accordingly for illnesses that require prompt high technology, highly trained specialist care for optimal outcome it seems likely that the weekend effect reflects lack of appropriate resources. However much emergency care mortality at weekends relates to illnesses such as infection and trauma where the technology and specialist care part of the pathway of care is apparently available.

- The hyper actuate stroke model introduced during the last two decades worldwide has created major resourcing and systems challenges but also more detailed data capture possibilities. Detailed analysis for stroke in the UK reveal that the mortality effect is more a time of day effect, with for example 30 day mortality showing no weekend effect but there is an out of hours effect at night most pronounced during week days[15]. The differential access to investigations has been long known in stroke[16]. However the registries created to define stroke care have also allowed us to understand just how great a factor coding error is in creating the 'weekend effect' from routine admissions data[17].

- It has been known for many years that seasonal influenza confers the greatest increase in risk of in-hospital mortality, followed by weekend admission, high hospital bed occupancy and that increasing nurse staffing levels decreases the absolute risk of mortality as the most effective potential intervention.[18]. However this translates into resource constraints that are not attractive political targets, as for example increasing hospital bed capacity which requires capital funding, tends to result in unmeet demand and diversion from other pathways of care filling the beds. Paying for nurses and their training is the single largest recurrent funding component in healthcare.

- Therefore the phenomenon has been attributed in some healthcare systems to reduced availability of senior clinical staff and reduced access to investigative services in hospitals at weekends[19] but on a whole system basis there is no causal evidence establishing this link[20]. However from in England experiments in redeploying secondary care medical manpower were launched in terms of contract change justified by a government manifesto commitment to reduce weekend deaths. As it transpired higher mortality rates amongst emergency patients admitted to hospital at weekends reflected a lower probability of admission [21] partially driven by lack of GP services at weekends and GP services had a manpower crisis due to lack of investment so could not address the issue, the impact of other change to produce the same ends is unknown. There are actually multiple complexities as data modelling trying to control for case mix always has limitations, association is not causation, and the issues causing the phenomena are much wider than healthcare. As of there is actually no statistical evidence in the UK that the lower availability of specialised senior staff at weekends impacts mortality or that increasing this ratio alone as an intervention as commenced decreases mortality[22]. No studies suggest junior doctor availability is more important than skilled nurses availability but this former issue can be seen to be easier to address in the context that shortages of both resources appear to be associated with poorer patient outcome and there is lower turnover of the doctor resource.

References

- ↑ Kostis WJ, Demissie K, Marcella SW, Shao YH, Wilson AC, Moreyra AE; Myocardial Infarction Data Acquisition System (MIDAS 10) Study Group. Weekend versus weekday admission and mortality from myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med.356(11):1099-109.

- ↑ Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays.N Engl J Med.345(9):663-8. Erratum in:N Engl J Med;345(21):1580.

- ↑ Saposnik G, Baibergenova A, Bayer N, Hachinski V. Weekends: A Dangerous Time for Having a Stroke? Stroke. Mar 8;

- ↑ Barba R, Losa JE, Velasco M, Guijarro C, Garcia de Casasola G, Zapatero A. Mortality among adult patients admitted to the hospital on weekends. Eur J Intern Med. Aug;17(5):322-324.

- ↑ Foss NB, Kehlet H. Short-term mortality in hip fracture patients admitted during weekends and holidays. British journal of anaesthesia;96:450-4. (Direct link – subscription may be required.)

- ↑ Aylin P, Yunus A, Bottle A, Majeed A, Bell D. Weekend mortality for emergency admissions. A large, multicentre study. Quality & safety in health care. Jun; 19(3):213-7.(Link to article – subscription may be required.)

- ↑ Aylin P, Alexandrescu R, Jen MH, Mayer EK, Bottle A. Day of week of procedure and 30 day mortality for elective surgery: retrospective analysis of hospital episode statistics. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 346:f2424.(Epub)

- ↑ Freemantle N, Richardson M, Wood J, Ray D, Khosla S, Shahian D, Roche WR, Stephens I, Keogh B, Pagano D. Weekend hospitalization and additional risk of death: an analysis of inpatient data. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. Feb; 105(2):74-84.(Link to article – subscription may be required.)

- ↑ Ruiz M, Bottle A, Aylin PP. The Global Comparators project: international comparison of 30-day in-hospital mortality by day of the week. BMJ quality & safety. Aug; 24(8):492-504.(Link to article – subscription may be required.)

- ↑ Mohammed MA, Faisal M, Richardson D, Howes R, Beaston K, Speed K, Wright J. Adjusting for illness severity shows there is no difference in patient mortality at weekends or weekdays for emergency medical admissions. QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians. Jul 12.(Link to article – subscription may be required.)

- ↑ McCallum IJ, McLean RC, Dixon S, O'Loughlin P. Retrospective analysis of 30-day mortality for emergency general surgery admissions evaluating the weekend effect. The British journal of surgery. Aug 12.(Link to article – subscription may be required.)

- ↑ Kostis WJ, Demissie K, Marcella SW, Shao YH, Wilson AC, Moreyra AE; Myocardial Infarction Data Acquisition System (MIDAS 10) Study Group. Weekend versus weekday admission and mortality from myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med.356(11):1099-109.

- ↑ Khoshchehreh M, Groves EM, Tehrani D, Amin A, Patel PM, Malik S. Changes in mortality on weekend versus weekday admissions for Acute Coronary Syndrome in the United States over the past decade. International journal of cardiology. May 1; 210:164-72.(Link to article – subscription may be required.)

- ↑ Kumar G, Deshmukh A, Sakhuja A, Taneja A, Kumar N, Jacobs E, Nanchal R. Acute myocardial infarction: a national analysis of the weekend effect over time. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. Jan 20; 65(2):217-8.(Link to article – subscription may be required.)

- ↑ Bray BD, Cloud GC, James MA, Hemingway H, Paley L, Stewart K, Tyrrell PJ, Wolfe CDA, Rudd AG. Weekly variation in health-care quality by day and time of admission: a nationwide, registry-based, prospective cohort study of acute stroke care Lancet 10 May DOI:

- ↑ Palmer WL, Bottle A, Davie C, Vincent CA, Aylin P. Dying for the weekend: a retrospective cohort study on the association between day of hospital presentation and the quality and safety of stroke care. Archives of neurology. Oct; 69(10):1296-302.(Link to article – subscription may be required.)

- ↑ Li L, Rothwell PM. Biases in detection of apparent "weekend effect" on outcome with administrative coding data: population based study of stroke. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 353:i2648.(Epub)

- ↑ Schilling PL, Campbell DA, Englesbe MJ, Davis MM. A comparison of in-hospital mortality risk conferred by high hospital occupancy, differences in nurse staffing levels, weekend admission, and seasonal influenza. Medical care. Mar; 48(3):224-32.(Link to article – subscription may be required.)

- ↑ NHS services, seven days a week forum. Summary of initial findings Dec NHS England

- ↑ Freemantle N, Ray D, McNulty D, Rosser D, Bennett S, Keogh BE, Pagano D. Increased mortality associated with weekend hospital admission: a case for expanded seven day services? BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 351:h4596.(Epub)

- ↑ Meacock R, Anselmi L, Kristensen SR, Doran T, Sutton M. Higher mortality rates amongst emergency patients admitted to hospital at weekends reflect a lower probability of admission. J Health Serv Res Policy May 6, doi:10.1177/1355819616649630

- ↑ Aldridge C, Bion J, Boyal A, Chen Y, Clancy M, Evans t, Girling A, Lord J, Mannion R, Rees P, Roseveare C, Rudge G, Sun J, Tarrant C, Temple M, Watson S, Lilford R. Weekend specialist intensity and admission mortality in acute hospital trusts in England: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 10 May DOI: